Controlling bacterial growth in fermentation with hurdle technology and survival analysis

This article is a nice intersection of some of the topics I've been thinking about lately: bacteria, food, and survival analysis, and part of a larger project I've been working on (stay tuned).

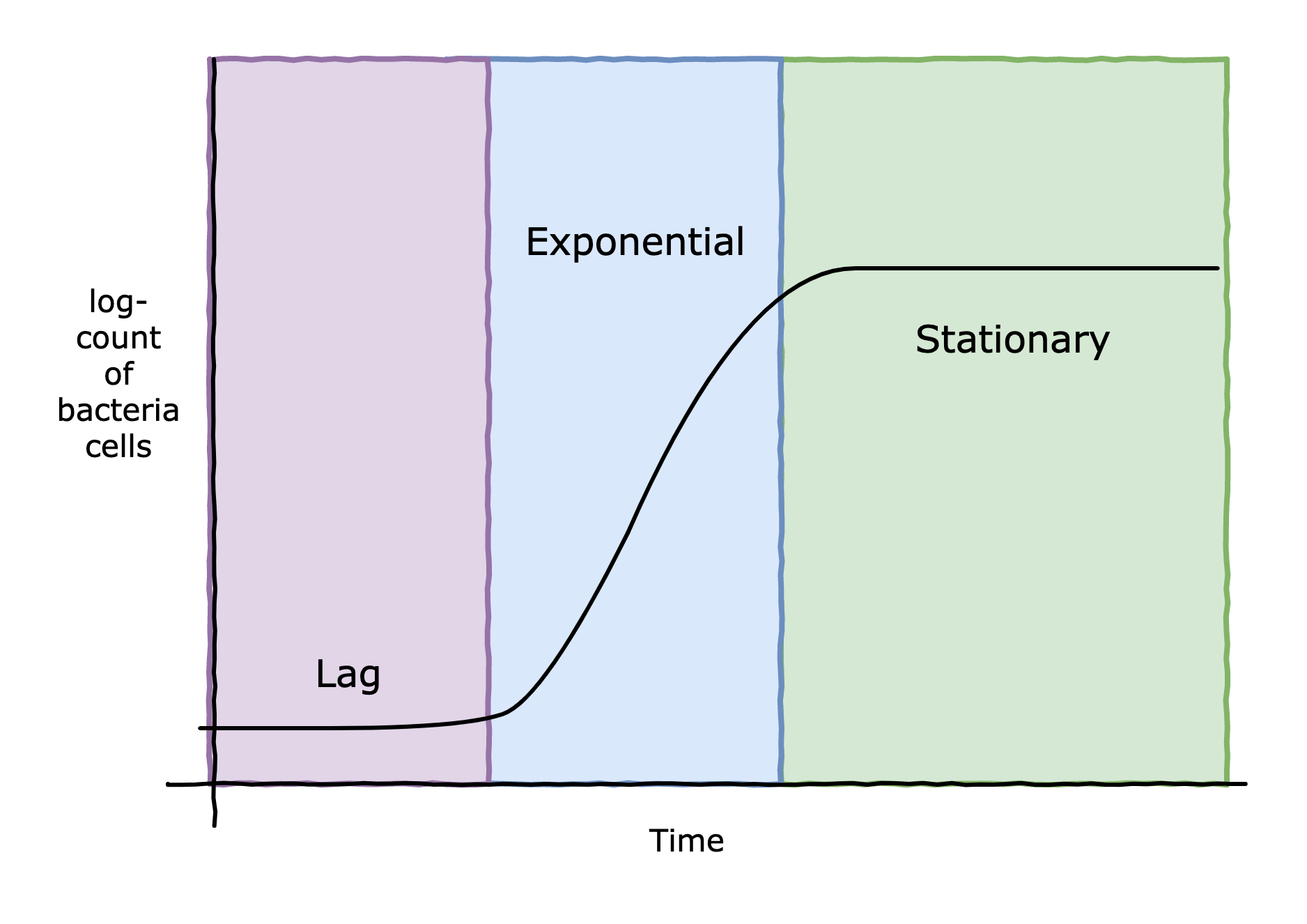

The bacteria C. Botulinum is responsible for creating one of the most dangerous chemicals known to man: botulinum toxin. If ingested, incredibly small amounts of this toxin can kill even a healthy person. Thankfully, food scientists and microbiologists have developed ways to control C. Botulinum. Any of the application of high acidity, high salinity, low/high temperature, oxygen-exposure can slow the growth of the bacteria, and in extreme amounts, destroy the bacteria. However, for food purposes, it is sufficient to slow the growth of the bacteria, typically by extending its lag period to an extremely long time. The lag period is a phase where a microorganism becomes accustomed to its new environment, before starting cell division (and entering the exponential phase of growth) - see figure below. For example, the reason why vinegar is used in home canning is to create an environment that is unfavourable (too acidic) for any remaining microbes (and there always are some) won't start multiplying. Vinegar isn't necessarily killing the bacteria, just extending its lag phase. Improper acidification in home canning is actually the cause of most botulism outbreaks in the Western world.

Hurdle Technology

The idea of hurdle technology is to create more than one unfavourable growth condition for bacteria (or their spores). This idea is that either there is a super-additive negative effect on the growth, or that one condition can be "relaxed" to improve sensory characteristics (ex: less vinegar, but more salt) and still achieve the desired control.

Hurdle technology is present in almost all foods, typically disguised as some preservation technique. Consider cheese: it has low water activity (moisture), stored at cool temperatures, and high acidity. All of these conditions are hurdles.

Fermentation

One concern that I often see beginner fermenters worry about is botulism. This is understandable: it's somewhat uncomfortable leaving a jar of vegetables out of the fridge for weeks, and then eating it. This goes against everything we have been taught about food safety. And though rare, botulism is deadly enough that the expected risk is high enough to cause worry.

However, hurdle technology is at play here. The idea is to use multiple hurdles, in this case salt, acid, and enough competing microbes, to effectively pause any botulism bacteria in their lag period. The salt is added in the brine, and the acid can be provided by the lactic acid bacteria or manually added to the brine. For brines below 6% NaCl, which almost all fermentation brines are, the lactic acid bacteria have essentially no lag period and very quickly enter their exponential phase [1]. However, C. Botulinum can survive moderate amounts of salt as well, and if present, could also start multiplying. What we'd like is to create an environment that extends the lag period of C. Botulinum far enough such that the lactic acid bacteria can completely out compete any C. Botulinum present. Let's get some data.

However, hurdle technology is at play here. The idea is to use multiple hurdles, in this case salt, acid, and enough competing microbes, to effectively pause any botulism bacteria in their lag period. The salt is added in the brine, and the acid can be provided by the lactic acid bacteria or manually added to the brine. For brines below 6% NaCl, which almost all fermentation brines are, the lactic acid bacteria have essentially no lag period and very quickly enter their exponential phase [1]. However, C. Botulinum can survive moderate amounts of salt as well, and if present, could also start multiplying. What we'd like is to create an environment that extends the lag period of C. Botulinum far enough such that the lactic acid bacteria can completely out compete any C. Botulinum present. Let's get some data.

The data comes from a 1983 paper on the effects of salt concentration and pH on C. Botulinum [2]. Below is a screenshot of the conditions of the trials (first and second columns) and observed lag period (third column).

We can see that we actually don't have many exact observations. Most observations are <1, meaning that the authors didn't observe the lag period end exactly, but instead noted that it happened sometime within the first day. Similarly, for some pH and salt concentrations, the lag period went past the authors' timeline of 85 days, so they recorded this as >85. This type of data is considered censored, so let's use survival analysis to analyze the relationship between pH, salt and lag periods.

Boot up Python

We are interested in determining the survival distribution of the lag period, conditional on pH and salt concentration. Don't get confused about the "survival" part here: we are not measuring survival of bacteria - we are using survival analysis, a technique for duration data, to model how long the bacteria is in its lag period. We have data that is both right-censored (>85) and left-censored (<1). We can encode this data by using two columns, one for a lower bound (which may be 0) and one for an upper bound (which may be infinity). For exact measurements, the lower and upper bound are equal:

from lifelines.datasets import load_c_botulinum_lag_phase

df = load_c_botulinum_lag_phase()

print(df) NaCl % pH lower_bound_days upper_bound_days

0 0 7.0 0.0 1.0

1 0 6.5 0.0 1.0

2 0 6.0 0.0 1.0

3 0 5.5 0.0 1.0

4 0 5.0 2.0 2.0

5 2 7.0 0.0 1.0

6 2 6.5 0.0 1.0

7 2 6.0 0.0 1.0

8 2 5.5 0.0 1.0

9 2 5.0 85.0 inf

10 3 7.0 0.0 1.0

11 3 6.5 0.0 1.0

12 3 6.0 0.0 1.0

13 3 5.5 2.0 2.0

14 3 5.0 85.0 inf

15 4 7.0 2.0 2.0

16 4 6.5 2.0 2.0

17 4 6.0 3.0 3.0

18 4 5.5 7.0 7.0

19 4 5.0 85.0 inf

20 6 7.0 85.0 inf

21 6 6.5 85.0 inf

22 6 6.0 85.0 inf

23 6 5.5 85.0 inf

24 6 5.0 85.0 infLet's use a Weibull survival regression model. That is, our functional form looks like:

$$ \begin{align}&P(\text{lag period} > t) \\ &= S(t\;|\;\text{pH},\text{salt%})\\ &= \exp{\left(-\left(\frac{t}{\lambda(\text{pH, salt%})}\right)^\rho\right)} \end{align}$$

where

$$ \lambda(\text{pH, salt%}) =\exp{(\beta_1\text{pH} + \beta_2\text{salt%} + \beta_0)} $$

The coefficients and \(\rho\) are to be estimated from the data. Fitting is done in lifelines:

from lifelines import *

aft = WeibullAFTFitter()

aft.fit_interval_censoring(

df,

lower_bound_col="lower_bound_days",

upper_bound_col="upper_bound_days")

aft.print_summary()

"""

<lifelines.WeibullAFTFitter: fitted with 25 total observations, 19 interval-censored observations>

lower bound col = 'lower_bound_days'

upper bound col = 'upper_bound_days'

event col = 'E_lifelines_added'

number of observations = 25

number of events observed = 6

log-likelihood = -25.70

time fit was run = 2020-04-12 13:20:30 UTC

---

coef exp(coef) se(coef) coef lower 95% coef upper 95% exp(coef) lower 95% exp(coef) upper 95%

lambda_ NaCl % 2.51 12.27 0.69 1.16 3.86 3.18 47.43

pH -4.87 0.01 1.48 -7.77 -1.98 0.00 0.14

_intercept 23.38 1.43e+10 7.16 9.35 37.41 11520.08 1.77e+16

rho_ _intercept -0.73 0.48 0.35 -1.41 -0.05 0.24 0.95

z p -log2(p)

lambda_ NaCl % 3.64 <0.005 11.81

pH -3.30 <0.005 10.01

_intercept 3.27 <0.005 9.84

rho_ _intercept -2.11 0.04 4.83

---

Log-likelihood ratio test = 31.94 on 2 df, -log2(p)=23.04

Looking at the coef column above, we can see that lower pH increases the lag period and a higher salt concentration increases the lag period. If we suspect there to be super-additive effects between salt and pH, we can try adding an interaction term. After doing so, the fit isn't very good, so we leave it out.

Aside: I found a handful of bugs (convergence errors, API mistakes) when doing this project, which is great, because it makes lifelines more robust for other users.

Now that we can connect pH and salt concentration to "probability of botulism growth", we can build a rule that minimizes a fermentation's risk to botulism. Specifically, if we provide the lactic acid bacteria (which has no lag period) a sufficient head start, we can rest assured they will out compete the bad bacteria and further acidify the environment. Let's say we want the probability of botulism growth in the first 6 hours to be less than 1%, which is more than enough time to give good bacteria a head start. In math:

$$ \begin{align} & P(\text{lag period} < 0.25) < 0.01\\ & \iff P(\text{lag period} > 0.25) > 0.99 \\ & \iff S(0.25) > 0.99 \\ & \iff S(0.25) = \exp{\left(-\left(\frac{0.25}{\lambda(\text{pH, salt%})}\right)^\rho\right)} > 0.99 \\ & \iff \exp{\left(-\left(\frac{0.25}{\exp{(2.51 \cdot \text{salt%} -4.87 \cdot \text{pH} + 23.38)}}\right)^{0.48}\right)} > 0.99 \\ \end{align} $$

Performing some algebra, and some rounding to make the final formula nicer, the above inequality is satisfied if:

$$2 \cdot \text{pH} - \text{salt%} < 9$$

If your initial brine satisfies this, you can be quite certain that the risk of botulism is nil. For example, if you want to decrease salt concentration by a percent, you should lower the pH by 1/2 a unit. Keep in mind, this is for a very conservative application, and even if this inequality is not satisfied, this does not mean that botulism will develop. This formula can be used for the most worried of individuals. There are of course many other ways to reduce the risk of botulism, but that's for a non-Data Origami article!